NASA’s Perseverance rover has launched from Cape Canaveral today on a US$2.7bn (£2bn) mission to Mars, carrying with it the first interplanetary aircraft, sophisticated instruments to search for signs of ancient life, and drill-to-core samples for eventual return to Earth.

Building on past discoveries at the Red Planet, the nuclear-powered robot will aim to become NASA’s ninth mission to land on Mars, and the first since the Viking landers of the 1970s charged with seeking evidence of life.

Launched during a two-hour window that opened today at 11.50am (GMT), a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket fired spacecraft away from Earth with a relative velocity of 24,785mph, or about 11km/sec. NASA’s Perseverance rover will now aim for the point in space where the Red Planet will be on 18 February 2021, the Mars 2020 mission’s designated landing date.

Perseverance is currently mounted on a rocket-powered descent stage that will eventually lower the robot to the Martian surface. That, in turn, is cocooned inside an aerodynamic shell and heat shield to protect the rover during entry into the atmosphere of Mars, when temperatures outside the spacecraft will reach 2,370°F (about 1,300°C).

Preparations for the launch had continued despite slowdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic. The Mars 2020 mission had to launch before mid-August in order to avoid a costly two-year delay until the next time Earth and Mars are in the right positions in the solar system.

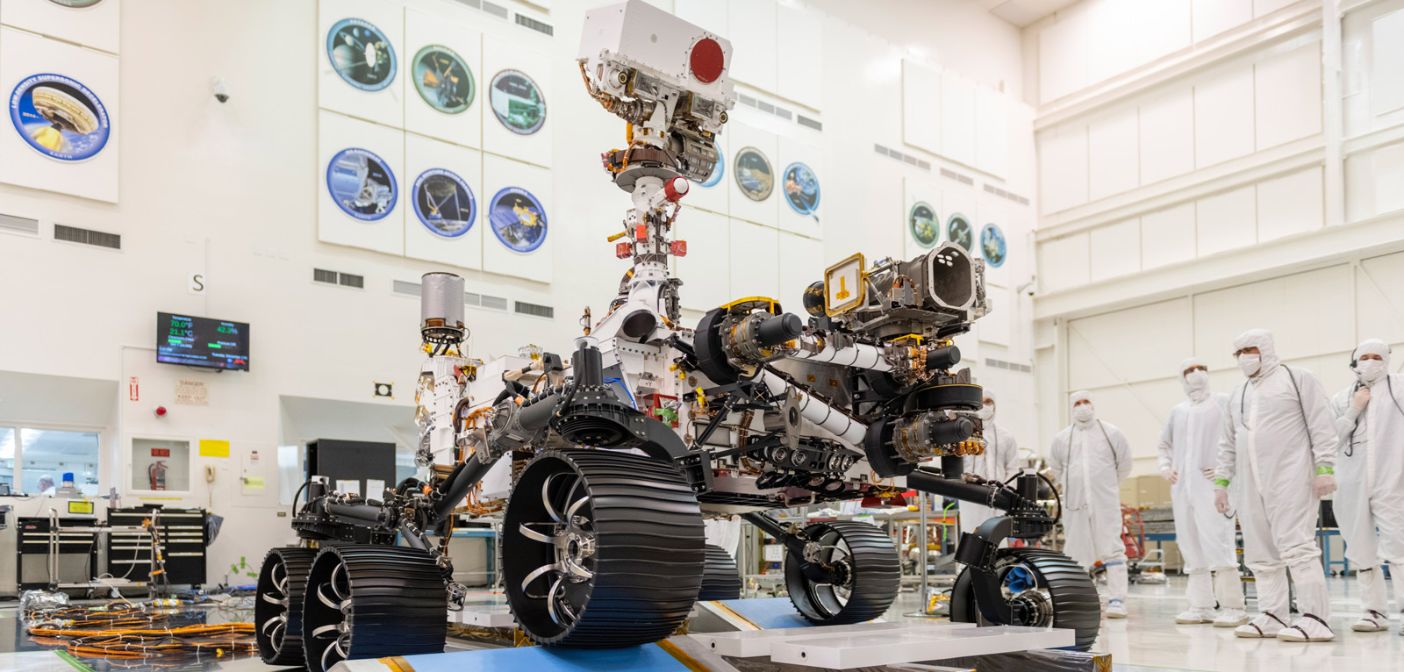

Hosting seven scientific payloads, a robotic arm, the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter, 25 cameras, and the first microphones to record sound on the Red Planet, NASA said the Mars 2020 mission is the most advanced robotic explorer ever sent into deep space.

A prime science goal of NASA’s Perseverance rover is to search for bio-signatures, markers left behind in Martian rocks by microbial life forms, assuming they existed. Should the mission be successful, scientists will be able to analyse rock samples gathered by Perseverance in laboratories on Earth for the first time.

In partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), rock and soil specimens gathered by Perseverance in 43 sample tubes will be sealed and tagged for return to Earth. This will allow scientists to cross-check rock and sediment specimens for contamination.

The 2,260 lb (1,025kg) Perseverance rover is about 10ft (3m) long, 9ft (2.7m wide), and 7ft (2.2m) tall. It has a 7ft-long (2.2m) robotic arm with a coring drill fixed on a 99 lb (45kg) turret on the end. The longer robotic arm will work in concert with a smaller 1.6ft-long (0.5m) robotic manipulator inside the belly of the rover, which will pick up sample tubes for transfer to the main arm for drilling.

According to NASA, the rover’s sampling system actually consists of three different robots. “Out at the end of our robotic arm — that’s the first robot — is a coring drill that uses rotary percussive action like we have used similarly and previously on Mars with the Curiosity mission, except rather just generating powder, this creates an annular groove in the rock and breaks off a core sample,” said Adam Steltzner, chief engineer on the Mars 2020 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

During each sample collection, the core sample will go directly into the tube attached to the drill. “That bit and the sample tube are brought back by the robotic arm — our first robot — into the second robot, our bit carousel, which receives the filled sample tube and delivers it to a very fine and detailed robot, the sample handling arm inside the belly of the beast, in which the sample is then assessed, its volume is measured, images are taken, and it is sealed and placed back into storage for eventually being placed in a cache on the surface.”

Assuming Perseverance’s mission is a success, and funding and technical plans remain on track, NASA and the ESA could launch missions as soon as 2026 with a European-built Mars rover to retrieve the specimens and deliver the material to a US-supplied solid-fuelled booster to shoot the samples from Mars into space.

A separate spacecraft provided by the ESA would then link up with the samples in orbit around Mars, then head for Earth before releasing a NASA re-entry capsule containing the Martian material to complete the first round-trip interplanetary mission no earlier than 2031.

Scientists will then analyse the samples for chemical signatures in the core samples, which might suggest life once existed on Mars.

NASA’s the Mars 2020 mission will also debut an array of new capabilities. “We’re making oxygen on the surface of Mars for the first time,” said Matt Wallace, the Mars 2020 mission’s deputy project manager at NASA’s JPL. “For the first time we have an opportunity to use autonomous systems to avoid hazards as we land, and that’s technology that will feed forward into future robotic systems and human exploration systems.

“We’re also carrying microphones for the first time. We’re going to hear the sounds of the spacecraft landing on another planet and the rover drilling into rocks and rolling over the surface of Mars. That’s pretty exciting.

“And for the first time, we’re going to have an opportunity to see our spacecraft land on another planet,” Wallace continued. “We’ve got 25 commercial ruggedised cameras that we’ve distributed essentially all over the spacecraft, and they will get high-definition video that we’ll bring back after we land on the surface from the entire landing activity — from the inflation of the parachute to the touchdown of the rover.”

NASA’s Perseverance rover is the third mission to Mars to launch this month, following the July 19 takeoff of the Hope orbiter developed by the United Arab Emirates in partnership with scientists at three US universities. On July 23, China launched its Tianwen 1 spacecraft, an all-in-one mission consisting of an orbiter, lander and rover. Both missions are the first probes from the UAE and China to head for Mars.