David Smith finds out how Stewart Miller, the newly appointed CEO of the National Robotarium, plans to turn the multimillion-pound facility into a globally recognised centre of excellence for robotics and AI…

As a fan of science fiction, Stewart Miller is aware of how dystopian stories about robots unsettle many people’s minds. In his role as the new chief executive of the £22.4m National Robotarium, based at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Miller wants to challenge the issue of mistrust by promoting the social and economic benefits of robots, as well as developing world-leading research projects.

The next era of robotics, he believes, will be dominated by cobots that live alongside humans. While the technology has the power to transform social care, healthcare and various other sectors, Miller believes mass public acceptance of the essential benevolence of robots is crucial.

“In science fiction, the more benign predictions show humans and robots working in harmony. I hope we can get to a point where we get so comfortable that we almost don’t see a distinction,” he says. “For young kids, who are exposed to robots in classrooms, acceptance will be easy. But for generations in their seventies and eighties entering care homes and coming into contact with a robot, it could be jarring.”

As soon as he saw the job specification, Miller, who was appointed in August, knew he had to apply. What attracted him was the National Robotarium’s pivotal role in developing advanced research while also partnering with industry to commercialise the technologies. “As I’ve worked for many years in both the private and public engineering sectors, I was amazed by how well it fitted my experience and interests. It was a no-brainer to apply,” he says.

Trained as a digital design engineer, Miller has worked for various aerospace companies, including 20 years for global giant Leonardo. He moved gradually over the years from purely technical roles into developing technologies and business opportunities. For the 12 months before his new role at the National Robotarium, he was chief technical officer for Innovate UK, gaining insights into how the British government encourages innovation and technology development.

Collaborative approach

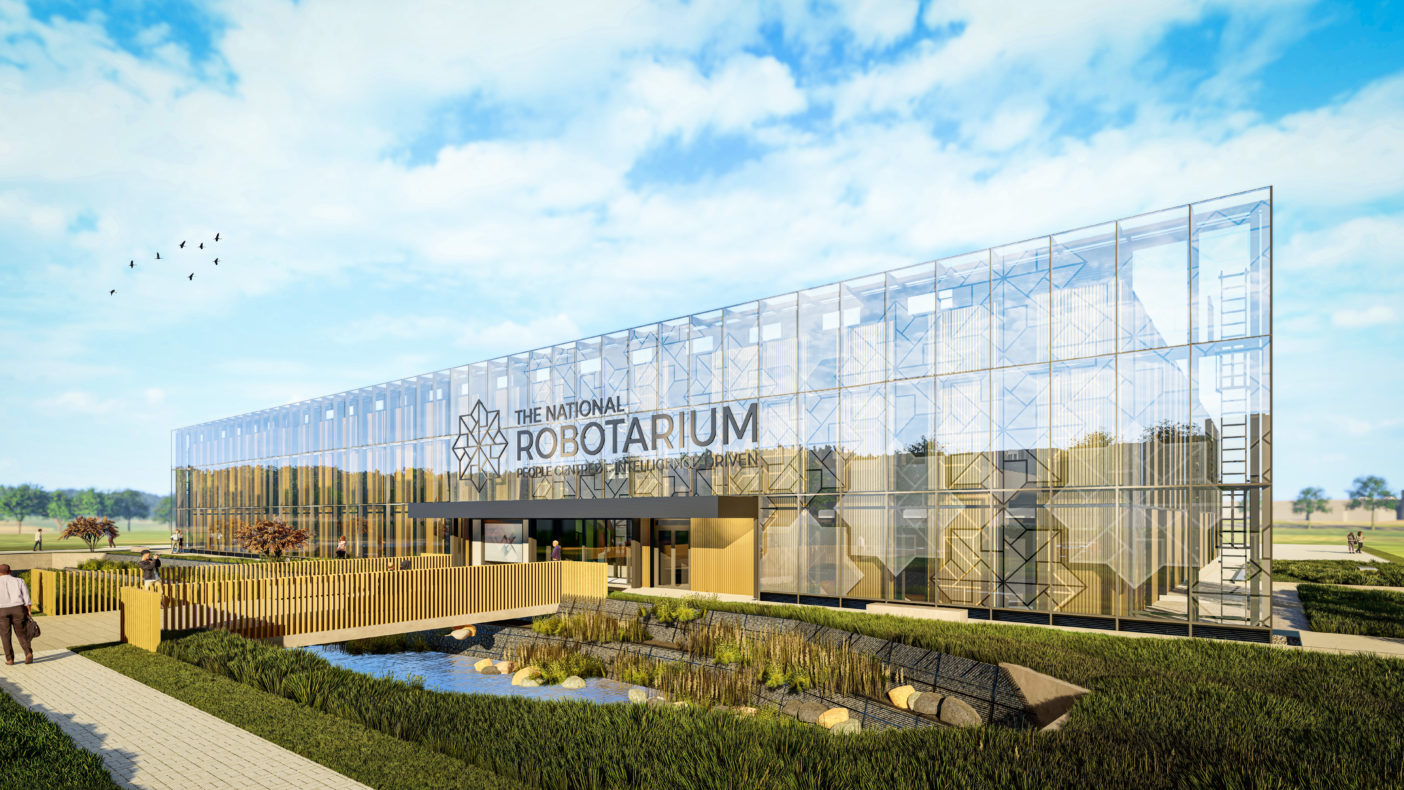

Upon completion, the National Robatorium will be the largest and most advanced facility for robotics and AI research in the UK. The centre is funded as part of the Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal and is a collaboration between Heriot-Watt University and the University of Edinburgh. It is expected to open in spring 2022 on Heriot-Watt University’s Edinburgh campus, but plenty of research projects have already begun. The 40,000ft2 building will house separate facilities for robotics and autonomous systems, human and robotics interaction and high-precision manufacturing. Key areas of research include hazardous environments, offshore energy, manufacturing, healthcare, human-robot interaction, assisted living and agri-tech. There will be dedicated laser labs, an autonomous systems laboratory, and a living lab for demonstrations in a realistic home setting.

According to Miller, much of the National Robotarium’s research will focus on the development of cobots operating in harmony with humans. “We’re seeing far more of a cobot approach. Up to now, robotics was predominantly about replacing humans, such as on automotive production lines. Now they’re going to work alongside humans in the social care and healthcare sectors, as well as in construction, factories, food processing and agriculture. There’s huge potential to augment and assist,” he says.

A recent research project undertaken at the National Robatorium’s assisted living lab illustrates the revolutionary potential of cobots in healthcare settings. At the end of September, the lab demonstrated an AI-powered telepresence robot for remote consultations. Health practitioners will be able to assess a person’s physical and cognitive health from any where in the world. “It will enable robot assistants in the home to monitor patterns of behaviour, such as if a person with a condition like Alzheimer’s is sleeping longer and not getting out of bed, or exercising. Remote carers can see through the robot’s eyes, move around the room and operate its arms to make assessments,” Miller says.

The telepresence robot also reveals the growing importance of AI in robotics research, he believes. The prototype will make use of machine learning and AI to collate and analyse data from smart home sensors to detect the patient’s daily activities. “The next generation of robots will be highly dependent on AI. It’s the area of research that needs the most work, not because we’re behind, but because it has the most potential. In social care, especially, the more sophisticated the AI, the more the interactions are likely to be humanlike. That’s essential as it will break down resistance to using robots,” he says.

Similar cobot technology is relevant to the National Robotarium’s research in various sectors, he says. In June, the National Robatorium introduced the first Spot robot for hazardous environments, for example. Developed by US outfit Boston Dynamics, the quadruped mobile robot has been fitted with telexistence technology allowing remote monitoring of a casualty’s vital signs. The team will also fit lidar sensors to the robot to build up a picture of its surroundings, enabling it to detect obstacles, such as rubble on construction sites. Meanwhile, the National Robotarium is developing a social robot that acts as a squash coach. It uses motion tracking sensors attached to the racket to monitor swings and provides technical feedback.

Public perception

As part of its mission to transform perceptions of robotics, the National Robotarium will encourage children from all backgrounds to consider it as a career. There will be a dedicated education hub inside the building for students to visit and Miller has targets for outreach over the next five years. “Inspiring the next generation is critical. I became interested in engineering as a child growing up in Scotland when I saw a Panorama programme called Now the Chips Are Down in 1978 about microprocessors. Even then, there were predictions about robot warehouse and autonomous vehicles that are becoming a reality now. Without that exposure, I wouldn’t have been aware of what microprocessors could do for mankind and wouldn’t have studied engineering. We’ll be talking less about the nuts and bolts and more about the benefits for society and the economy,” he says.

The National Robotarium’s collaborations will be with businesses of all sizes, from household names to innovative start-ups. Miller says gaining access to facilities such as the living labs and validations suites will help British SMEs to prototype ideas. As Miller explains, “The National Robotarium is a business proposition. The government has put money in and expects benefits on the form of economic growth and social benefits.”

Strong connections

The potential for the National Robotarium to make a difference is evident from the success of a similar centre in Denmark, Miller believes. The Danish Technological Institute has been instrumental in establishing Denmark as a global leader in robotics’ research despite the country’s population of fewer than six million. Denmark ranks seventh in the world for global robot density and there is a strong focus on the city of Odense, known as the Silicon Valley of Robotics. “We’ve been studying a few national research centres and Denmark’s is one of the most impressive. It’s built up a cluster of businesses and start-ups over the past 10 years, and shows what we could achieve.”

Miller is keen to develop strong connections with the leaders of other major UK centres for robotics and AI research. These include the RACE and RAIN hubs, which conduct robotics research in the atomic and nuclear energy sectors, as well as the Bristol Robotics Laboratory and The Alan Turing Institute for AI. “I’m keen to get a multiplication effect going so the UK as a whole is punching above its weight. As CEO, it’s incumbent on me to have those discussions and build a national effort. We need to work together to catch up on countries that are ahead of us, like China, the USA, Japan and Korea. There’s a lot of intellectual capital in the UK, but we’ve not always shown as much business savvy. If we work together, we’re more likely to become globally significant,” Miller concludes.

An ideal for living

The National Robotarium has built the world’s first open and remote assisted living laboratory to test robotics solutions for assisted living. The lab operates like a real flat with a kitchen, living room, bathroom and bedroom.

The Robotic Assisted Living Testbed (RALT) has connected sensors, domestic robots and other technologies to help care practitioners, designers and end-users to test the usefulness of assisted living technologies. The laboratory is equipped to offer real-time interaction with its sensing, automation and robotic equipment, over the internet.

Dr Mauro Dragone, an assistant professor and director at RALT, says: “It provides a platform that researchers, technology and industry users can use to co-create technology, where time and distance are no longer barriers – any time, any place access. The aim is to catalyse collaborations to more quickly develop innovative concepts of assistive living technology to be considered for mass-market roll-out.”

One project being trialled at the RALT is the ‘Earswitch’, which can be used to operate multiple devices using an ear muscle alone. According to its creator, primary care practitioner Dr Nick Gompertz, this could significantly improve the independence of thousands of individuals with a range of assisted living needs. As well as controlling simple switching commands, the team now intends to combine biometric data from the Earswitch with smart home monitoring data to build a picture of a person’s health, daily routines and activities in the home.