The rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI) products like the text-generating tool ChatGPT has politicians, technology leaders, artists and researchers worried. Meanwhile, proponents argue that AI could improve lives in fields like healthcare, education and sustainable energy.

The UK government is keen to embed AI in its day-to-day operations and set out a national strategy to do just that in 2021. The aim, according to the strategy, is to “lead from the front and set an example in the safe and ethical deployment of AI”.

AI is not without risks, particularly when it comes to individual rights and discrimination. These are risks the government is aware of, but a recent policy white paper shows the government is reluctant to increase AI regulation. It is difficult to imagine how “safe and ethical deployment” can be achieved without this.

Evidence from other countries shows the downsides of using AI in the public sector. Many in the Netherlands are still reeling from a scandal related to the use of machine learning to detect welfare fraud. Algorithms were found to have falsely accused thousands of parents of child benefits fraud. Cities across the country are reportedly still using such technology to target low-income neighbourhoods for fraud investigations, with devastating consequences for people’s wellbeing.

An investigation in Spain revealed deficiencies in software used to determine whether people were committing sickness benefit fraud. And in Italy, a faulty algorithm excluded much-needed qualified teachers from open jobs. It rejected their CVs entirely after considering them for only one job, rather than matching them to another suitable opening.

Public sector dependence on AI could also lead to cybersecurity risks, or vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure supporting the NHS and other essential public services.

Given these risks, it’s crucial that citizens can trust the government to be transparent about their use of AI. But the government is generally very slow, or unwilling to disclose details about this – something the parliamentary committee on standards in public life has heavily criticised.

The government’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation recommended publicising all uses of AI in significant decisions that affect people. The government subsequently developed one of the world’s first algorithmic transparency standards, to encourage organisations to disclose to the public information about their use of AI tools and how they work. Part of this involves recording the information in a central repository.

However, the government made its use voluntary. So far, only six public sector organisations have disclosed details of their AI use.

Public sector AI use

The legal charity Public Law Project recently launched a database showing that the use of AI in the UK public sector is much more widespread than official disclosures show. Through freedom of information requests, the Tracking Automated Government (TAG) register has, so far, tracked 42 instances of the public sector using AI.

Many of the tools are related to fraud detection and immigration decision-making, including detecting sham marriages or fraud against the public purse. Nearly half of UK’s local councils are also using AI to prioritise access to housing benefits.

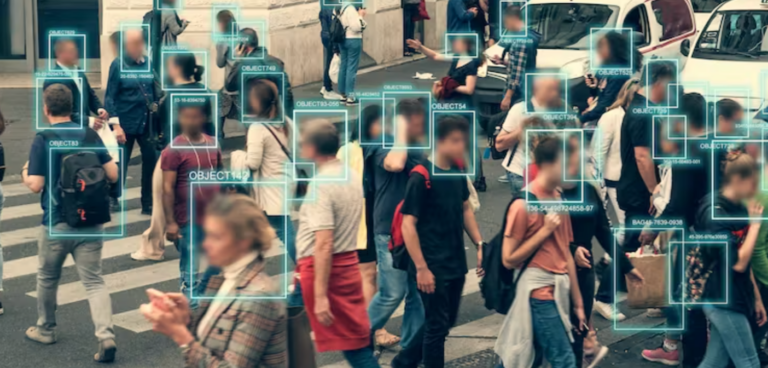

Prison officers are using algorithms to assign newly convicted prisoners into risk categories. Several police forces are using AI to assign similar risk scores, or trialling AI-based facial recognition.

The fact that the TAG register has publicised the use of AI in the public sector does not necessarily mean that the tools are harmful. But in most cases, the database adds this note: “The public body has not disclosed enough information to allow proper understanding of the specific risks posed by this tool.” People affected by these decisions can hardly be in a position to challenge them if it is not clear that AI is being used, or how.

Under the Data Protection Act 2018, people have the right to an explanation about automated decision making that has legal or similarly significant effects on them. But the government is proposing to cut back these rights too. And even in their current form, they aren’t enough to tackle the wider social impacts of discriminatory algorithmic decision-making.

Light-touch regulation

The government detailed its “pro-innovation” approach to AI regulation in a white paper, published March 2023, that sets five principles of AI regulation, including safety, transparency and fairness.

The paper confirmed that the government does not plan to create a new AI regulator and that there will be no new AI legislation any time soon, instead tasking existing regulators with developing more detailed guidance.

And despite just six organisations using it so far, the government does not intend to mandate the use of the transparency standard and central repository it developed. Nor are there plans to require public sector bodies to apply for a licence to use AI.

Without transparency or regulation, unsafe and unethical AI uses will be difficult to identify and are likely to come to light only after they have already done harm. And without additional rights for people, it will also be difficult to push back against public sector AI use or to claim compensation.

Put simply, the government’s pro-innovation approach to AI does not include any tools to ensure it will meet its mission to “lead from the front and set an example in the safe and ethical deployment of AI”, despite the prime minister’s claim that the UK will lead on “guard rails” to limit dangers of AI.

The stakes are too high for citizens to pin their hopes on the public sector regulating itself, or imposing safety and transparency requirements on tech companies.

A government committed to proper AI governance could create a dedicated and well-resourced authority to oversee AI use in the public sector. Society can hardly extend a blank cheque for the government to use AI as it sees fit. However, that is what the government seems to expect.![]()

Albert Sanchez-Graells, professor of economic law and co-director of the Centre for Global Law and Innovation, University of Bristol. It was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.